Massinissa Selmani has set up his studio about 15-minutes north of the historic center of Tours in France. To get there, one must simply drive across the Loire region and its ever-changing scenery. Set on the ground floor of a former pinball machine repair shop, it looks directly out onto a calm street. In this working-class residential neighborhood, people sometimes wonder what this slender, dark-haired man can be up to with his trestles on the pavement. It is May, and the artist is working on the set of works he will present in autumn for the prix Marcel Duchamp.

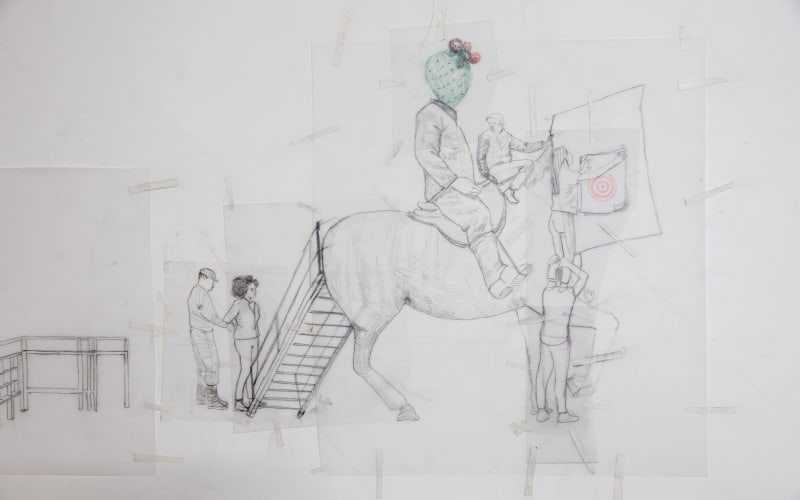

The 43-year-old artist is savoring the opportunity to take part in the event with genuine modesty. Drawing is his field of experimentation, whether he is working on paper, tracing paper, on short animations, or even in space. Based on images from archives of news clippings, he builds 'drawn forms' in a surrealist style of collage and collision. He collects incongruous elements, removes them from their context and juxtaposes them by staging small, enigmatic scenes, somewhere between tragedy and comedy, where the absurd is never very far away. 'I like the flexibility of drawing, its almost dreamlike, subjective aspect, and the relationship with simple materials.' His sketchbooks, always within reach, are full of outlines, little drawings - clouds, watering cans, stairs, cacti - though he is not really sure why. Around us, the large squares of paper hanging on the walls or spread out over drawing tables attest to his intense creative production. In Selmani's words, he works slowly, 'at a turtle's pace.' But for the prix, 'the solution was already in my sketchbooks,' he says.

He is now a widely acclaimed artist: he won the jury's Special Mention award at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, and six of his drawings entered the Musée National d'Art Moderne's collection the same year. But Selmani started out as a computer scientist: 'Both of my brothers are computer scientists. I liked typing code,' he says, pragmatically. The artist, who was born into a working-class family in Algiers, studied computer science at the University of Tizi-Ouzou, 'first and foremost to reassure my family.' But as far back as he can remember, he has always drawn.

'As a child, I spent my time after school drawing and playing football,' he says. 'I lived in a working-class neighborhood in the center of Algiers. I was always outside, we were protected by the neighborhood.' In the 1990s, Algeria experienced a terrible civil war, which left its mark on the entire country. 'Looking back, I realize that my first exercise in critical thinking was through humor and editorial cartoons. My father, who managed a copy shop, was always an avid newspaper reader. At that time, with all the violent headlines, press cartoons provided an opportunity to laugh, before having to face it all. It's an almost philosophical approach, a way to create a healthy distance, which, I believe I've kept in my work.' When he was around eight years old, he took lessons at the local youth center, with Algerian classics playing in the background. After moving to Kabylia, he continued to draw at the Tizi Ouzou cultural center at the age of 14. He was talented and planned to attend the School of Fine Arts in Algiers, 'but it was extremely expensive.' So, computer science it was.

During his first years at school, Selmani produced a huge number of drawings mocking terrorists. 'I needed to get things out,' he explains simply. He felt a bit lost, but enthusiastic, and was quick to adapt to his new surroundings: 'It was the first time I'd left Algeria, but I felt almost less out of place in Tours than when I was in the west of Algeria for the first time! Algeria is a continent: it's huge, with great diversity. You fall in love with the Loire quickly - it exudes this strange sense of tranquility that at times seems unreal to me,' he adds. One of his mentors at the School of Fine Arts was Suzanne Lafont. The photographer, who works in the area of documents and archives, led him to reflect on his practice: 'She's the one who helped me realize some of the things I was doing already, unintentionally, like lightness, the direct relationship with certain materials, etc. She helped me structure things, and gain a broader visual culture. I was then lucky enough to be mentored by Marc Monsallier, with whom I still speak regularly and maintain a close friendship.'

While he readily admits that he had only limited access to books in his youth, Selmani cites Honoré Daumier among his earliest influences. Then came New Yorker cartoonists, including Saul Steinberg, his 'ultimate model,' who he discovered at art school. For his exhibition with the other nominees, which he has titled, 'Une parcelle d'horizon au milieu du jour' ('A Patch of Horizon in the Middle of the Day'), Selmani warns: 'I haven't imposed a specific narrative. It's a progression, made up of situations suspended in space and time, where people may feel disoriented, despite recognizing things that seem to be familiar. The question of ellipsis, which I've addressed both formally and metaphorically, will be present.' As usual in his work, here too, everything is done in a spare, pared-down style. As he says, 'I spend more time taking things away than adding them. I love creating with very little, like Giuseppe Penone or Dan Perjovschi. I feel that the possibilities are endless. Drawing allows for an autonomy that suits me, I need to be able to work everywhere and all the time.'

His installation includes a small model boat, a globe, and an animated video played on a loop, with a bird, because, as he says, 'I don't know how to make something with a beginning and an end.' In his pencil drawings, there is a cactus here, a watering can there, and people, whose positions have been reproduced on tracing paper, then on paper, taken from press cuttings (he collects old editions of Le Monde and Libération). There are also forms derived from architecture (he is a fan of the working drawings of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Claude Parent), which tend towards the absurd -'unfathomable places' - as he describes them. Violence is a subtext, but never shown. To understand Selmani's works, one must come closer, as if to enter the drawing: 'I ask viewers to make an effort. I find showy works frustrating, since once you've got past the initial phase of astonishment, there's a risk that not much will remain. It's true that my works are somewhat subdued at first glance,' he says. Then, in an amused tone, he adds, 'sometimes people think there's a hidden meaning in some of my drawings, but there isn't.'

Yet in 2005, he made up his mind and applied to just one fine-arts school - in Tours - 'because a friend had talked to me about the city.' He was preselected, but without the money to pay for a plane ticket or visa, he could not attend the interviews. 'The professors gave me a chance. But it wasn't easy. I needed some time to adjust and I had to start reading extensively, basically overnight. But I loved it.' He graduated in 2010. Behind his seemingly calm exterior, Selmani has a pugnacious spirit. As he says, 'I always knew I would become an artist.'

FULL ARTICLE HERE

Prix Marcel Duchamp

Centre Pompidou, Paris

October 4, 2023 – January 8, 2024