M’barek Bouhchichi

Black Seeds, البذور السوداء

Les Graines Noires presents a new body of work by M’barek Bouhchichi that reflects on the connections between Blackness and movement, drawing on past and ongoing histories, including trans-Saharan slavery, the Atlantic slave trade, and contemporary Afro-Mediterranean migrations.

The artist uses plants as vectors for his study of centuries of migration and displacement across desert and sea. In botany, a diaspore is a unit of plant dispersal that consists of a seed or spore along with the structures that assist in spreading it. Seeds stand at the start of a ceaseless journey. In this body of work, they summon possibilities of survival thanks to the transmission of ancestral knowledge. They also point to the multiplicity of potential trajectories—each seed grows differently depending on the soil where it is planted, and its plant in turn produces new seeds adapted to its environment.

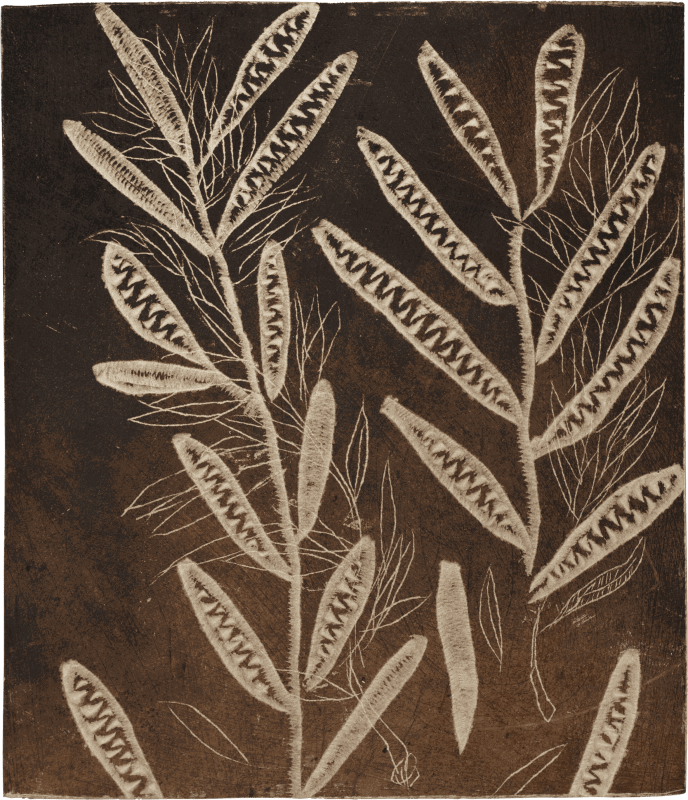

In Herbarium (2025), Bouhchichi draws inspiration from his visits to maroon communities—groups formed by formerly enslaved people who fled to remote areas in order to create autonomous societies. One series of nine engravings on alabaster stone tiles depicts plants found in Quilombo Kalunga in Brazil. A second series shows plants from the village of Khandaq ar-Rayhan near Chefchaouen, Morocco. Relying on knowledge passed down across generations, plant literacy is a cornerstone of maroon sovereignty, essential as it is for subsistence and healing. In addition to offering a botanical portrait of each group as seen from the ground, the work establishes a connection between these distant diasporic communities. This crucial intervention speaks to Bouhchichi’s overall artistic project: it inscribes North Africa within a global geography of Blackness.

Inspired by traditional navigation tools used in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean, Stick Charts (2025) maps the journey of two people who crossed the Sahara Desert, as reconstructed by the artist from their oral testimonies. Bouhchichi employs a syntax of maritime navigation to translate trans-Saharan crossings. The works are made out of brass casts of eucalyptus branches and cowrie shells. Originally from Australia, the eucalyptus tree was introduced to Africa in the 19th century by Western colonial settlers. Today, although common in countries like Morocco and Tunisia, it is poorly suited to their climates and contributes to soil drying—a reminder that imperialism forcibly uproots and relocates both human and non-human lives, in total disregard of all contexts. Paradoxically, North African eucalyptus forests currently provide shelter to people on migration trails, offering them a place to hide and rest before their final push toward the Mediterranean. As for cowrie shells, they were introduced into West Africa by Arab traders in the 8th century and used as currency for many centuries, including in the trans-Saharan trade. In Stick Charts, the shells indicate points on the road where migrants had to make payments to be granted passage; they signal obstacles on their itinerary that are also doorways into the future. A migrant journey is a complex network of spatial paradoxes.

Botanical semantics pervade most of the works in the exhibition. The brass sculpture Vegetal Man (2025) features three agave plant stalks. The agave blooms and produces seeds only once at the end of its life. After flowering, the plant dies but leaves seeds and shoots behind, allowing for new growth and ensuring the species' survival. Its death allows for multiple lives to bloom. For Bouhchichi, the agave’s life cycle resembles the fate of those who decide to cross the Sahara and the Mediterranean Sea in pursuit of a better life for themselves and their kin. Collective survival requires individual sacrifice. Vegetal Man tells a story where torment and mourning are ever-present in Black lives, but where rebirth and transmission never cease.

The legend of Boussaadia, referenced in Boussaadia (2025) and Saadia (2025), further touches on the experiences of displacement and othering that come with migration journeys. According to legend, Boussaadia [Father of Saadia] is a hunter from the Sahel whose daughter was kidnapped by slave raiders on their way north. He sets out on a journey across the desert to retrieve her. Weeks later, having arrived in Tunis exhausted and destitute, he resorts to begging in the streets while singing his sorrow. Boussaadia has become a tutelary figure in the Tunisian Stambeli tradition. A music-infused healing ritual based on spirit possession, Stambeli is mainly performed by descendants of displaced Sub-Saharan people organized into brotherhoods. Similar traditions are practiced across the Maghreb, such as Gnawa in Morocco or Diwan in Algeria. In Stambeli mythology, Boussaadia is both a wanderer and a guide, a figure around whom people gather. He is summoned as a medium into an esoteric world where Muslim saints and spirits from other African traditions manifest. Boussaadia (2025) consists of three hollow sculptures made of burnt wood, referencing different guembri shapes, as found in Morocco, Tunisia, and Mali. The guembri, a three-stringed, bass-sounding lute whose sacred sounds call in the spirits, is the main instrument of gnawa and stambeli ceremonies. Presiding over the rhythm and tonality of the performance, it conjures a repossession of the self and a gathering of the tribes. With its charred, hollowed-out guembris, Boussaadia insists on the process of dispersal and loss, evoking a longing for wholeness.

Such movements of scattering and regrouping are rendered in Seedings (2025), a series of ten drawings on paper made out of tree bark and recycled textiles. Bouhchichi employed traditional Tunisian hargous, a black ink used for temporary hand and face tattoos, in addition to an ink of his own creation, made out of date pits, gallnuts, and gum Arabic. The rustic paper and natural inks exude a sense of intimacy with the land. The drawings depict forms of pre-colonial West African currency, derived from blade-shaped tools and weapons. While the objects appear whole at first glance, a closer look reveals that the artist constructed them from countless seed-like dots. Suggesting strength and power found in unity, the works also evoke fugitive trajectories of migration that have the potential to evade control.

Relatedly, I Am Here (2025) replicates the ceramic jars used in Gougou, a musical and dance ritual practiced by Black populations from the Zarzis region, Tunisia, where performers stack clay jars on their heads while dancing. In I Am Here, the jars are inscribed with verses from a poem titled “الحراقة ” [The Burners, or clandestine migrants] by M’barek Toumi, a poet from the Ghbonten tribe in South-Eastern Tunisia. By way of this juxtaposition, Bouhchichi makes clear the fundamental connection between the ongoing tragedy of Mediterranean crossings and the longer history of trans-Saharan displacement.

Whereas Boussaadia is a known figure in Tunisian culture, Saadia, his abducted daughter, is absent from representation. She is synonymous with absence. With Saadia (2025), Bouhchichi attempts to give her a body. The work features two sculptures reproducing the same Neolithic object: a small, abstract female figurine from around 4,000 BCE, found in Kadruka, Sudan in the 1980s during a landmark dig in African archaeology. One of the sculptures is made from black Aziza marble, sourced from Tunisia, and the other from white Italian Carrara marble. This doubling trope recurs throughout the exhibition. Bouhchichi plays with variations of the same object via color, material, or texture. Such doubling indicates a contrast between two states of a body, or an idea of movement from a point of departure to a point of arrival. In the case of Saadia, the Carrara marble hints at Greco-Roman sculpture and the way it stands in for whiteness, deemed exclusively worthy of representation. The locally sourced black marble contests this narrative and proposes a different representational ethic. By hosting a transposition of the Kadruka figure, it inscribes Sudanese poiesis into Tunisian visuality.

Bouchichi’s use of materials is always intentional. His artworks embody complex ideas through material choices. Stick Charts and Vegetal Man, for instance, were fabricated using brass—an alloy of copper and zinc—, while Agave Seeds (2025) is made of nickel silver, a blend of copper, zinc, and nickel. Copper, a mineral and a pure chemical element, was historically used as a medium of exchange in the Sahel region, copper metallurgy being native to Niger and Mauritania. It is a mineral associated with circulation and transaction, as well as ritual and healing. Using copper alloys is a way for the artist to suggest the promise of transformation that the experience of migration entails. For all his endeavors towards instituting a Black space of representation, Bouhchichi refuses all ideas of racial purity. Marked by physical displacement and existential placelessness, Black life is inherently multiple and, as such, must be thought of in relation. Blackness cannot be reduced to a single model. The artwork Black Seeds (2025), a display of eight imaginary seeds, reflects this conceptual thread. Against the homogenizing pressures of marginalization, the task of the artist is to invent forms that convey the living multiplicity of the Black experience.

The artist extends heartfelt thanks to the many producers and master craftsmen whose work were instrumental in the realization of this exhibition. Special thanks go to: Yadh Beji, Ezzedine Ben Abdelali, Abdeljalil Aït Boujmiaa, Abdelatif Boujan, Marwen El Haj Sassi, Slim Gharbi, Mohamed Ghoulfani, Youssef Hachmi, Mabrouk Nemri, Brahim Taliouin as well as the Selma Feriani Gallery team—Haythem Aydi, Hedi Ben Chaabane, Tijani Ben Hassine, Selma Feriani, Rania Hentati, Racha Khemiri, Sawsan Kraiem, Najet Mansouri, Insaf Mejri—for their invaluable support.

Omar Berrada & Beya Othmani

September.2025.

Bios of curators

Omar Berrada is a writer and curator whose work focuses on the politics of translation and intergenerational transmission. He is the author of Clonal Hum, a book of poems on “invasive species” (2020), and the editor or co-editor of several volumes, including The Africans, on racial dynamics in North Africa (2016); La Septième Porte, a posthumously published history of Moroccan cinema by Ahmed Bouanani (2020); and Another Room to Live In, a trilingual (non-)anthology of Arabic poetry (2024). His writing was featured in numerous exhibition catalogs, magazines, and anthologies, including Frieze,Bidoun, Mizna, Asymptote, and The University of California Book of North African Literature.

Beya Othmani is an art curator. She currently serves as the C-MAP Africa Fellow at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), where she researches contemporary African art from the late 20th century, develops programs, and co-edits the digital platform post.moma.org. Othmani has curated projects for organizations such as MoMA, The Ford Foundation Gallery, the Ljubljana Graphic Arts Biennial, rizhome Gallery, Dak’Art, SAVVY Contemporary, among others. Her recent curatorial projects have explored various topics including feminist modes of creative resistance, post-colonial histories of printmaking, and racial constructs in the arts in post-colonial Africa.