“I have lived on the land long before swords turned man into prey”

Mahmoud Darwish

In the quest to explore the boundaries of land—those shaped by war, colonization,

militarization, and migration—this exhibition calls for a reconsideration of what it means to

inhabit spaces that have been mapped, claimed, and scarred, yet never fully contained. What

does it mean to walk on land, to trace its tactility, its undercurrents, and the histories it

accumulates? In the act of treading, is there an attempt to reclaim or redefine the very

territory that history has sought to conquer? Through videographic reflections, these works

capture the blurred and shifting contours of certain territories, offering a reconsideration of

how we experience and represent the lands we occupy. The map, in this context, is not an

absolute authority but rather a tool of interpretation, a stimulus for reflection. If image-

making serves as a way to confront precarious histories, then memory, too, becomes a

method of negotiating these contested landscapes, while the mapping of spaces in the videos

activates the respective territories.

As the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish once wrote, “I have lived on the land

long before swords turned man into prey,” reminding us that the land precedes all else, that

it bears witness to forces that seek to dominate it, and yet, it endures. It is with this perspective

that we approach territory here as the central protagonist. The landscape is its pivot,

assuming form in relation to time, memory and subjectivity. Territory holds within it silent

narrations—zones of passage, of crossings, and dislocations. As the philosopher and poet

Édouard Glissant observed, “our landscape is its own monument: its meaning can only be

traced on the underside. It is all history”.1 Through the language of moving image, the artists

trace landscapes not as static settings, but as dynamic protagonists: terrains shaped by time,

conflict, and survival. The land becomes both witness and actor: it is at once deeply personal

and irreducibly historical.

In this sense, the exhibition orchestrates moments of interaction between the

territories captured by different artists, who intimately and collectively map their interior

geographies in an effort to reclaim and destabilize these spaces, moving them beyond

imaginary constructions. It brings together heterogeneous visions in a site of engagement,

without necessarily blending or indexing them. Rather, it is an invitation to dwell in the

ambiguity of place—where the landscape is fragmented, layered, and ever alive.

Each landscape holds within it a complex collection of images—personal and

collective stories shaped by the resilience of those who inhabit it. Yet, these lands are not

passive backdrops but are active agents in the narratives of their people. By guiding our

perception through multiple lenses, they offer more than documentation. They are

interventions that breach time between the act of remembering and reinhabiting. They

collect a choreography of displacement and return. They call on us not simply to look and

observe, but to listen, to feel, and to remember otherwise. Embedded within each film, the

landscape becomes a medium for personal or collective recounts, broadcasting a dialogue

between the interiority (subjective experience) and the exteriority (physical or historical land) of

space. In doing so, the land ultimately speaks for itself, and we are asked to step back, to step

in, alternately, to traverse this projected choreography; to seek contact with these

surrounding locations while allowing ourselves to be transposed into the emitted images, to

1 Édouard Glissant, and J Michael Dash. Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays . University Press of Virginia, 1999, p. 11.be affected by these chronicles, and to virtually and viscerally tread places that are both here

and there.

Zineb Sedira

Les terres de mon père/ The Land of my Father (2016)

Country: Algeria

Is it legitimate to want to define the limits of a territory, or does this amount to removing them

from the only domain where they can become fulfilled: the interiority of the one who expresses

them, in this case her father? And if this is the case, how, in a respectful way, to map the notion

of territory? Every effort of spatialisation is, for her father, at once mental and physical. Walking,

her father traces out his land both mentally and physically. Experience plays a fundamental role

in the tracing of a territory. Zineb Sedira plays with this divide between ‘interiority’—the mental

apprehension of the world—and ‘physicality’—the physical materialisation of a territory. Is not

the notion of territory inseparable from the experience of the body? The two heterogeneous

notions of body and territory seem here, in the experience of her father, consubstantial with the

representation of land. A perception of territory at once precise and hazy emanates from such a

standpoint.

Kamal Aljafari

UNDR (2024)

Runtime: 15’

Country: Palestine

Helicopter footage examines the desert, surveying ancient natural formations and human

interventions. Dynamite changes the face of the land. Farmers work their fields. Children play

hide-and-seek. Employing archival footage, UNDR constructs an eerie narrative of calculated

incursion. We cannot help but recall that Palestine remains a land subjected to aerial

surveillance that seeks to appropriate the landscape.

Azzedine Saleck

Dune (2022)

Country: Mauritania

Runtime: 8’

“Above the land

Across the sand

The things I’ve seen

The ways I’ve been”

A conversation between Bah ould Saleck and Mohamedou ould Salahi, respectively the artist’s

father and a former Mauritanian detainee who spent 12 years in Guantanamo in the hands of

the CIA.

A dialogue between two Mauritanians about the time against the backdrop of images of a loads

of sand in the desert, suggests that possibly and despite human efforts the landscape escapes us

and cannot be conquered.

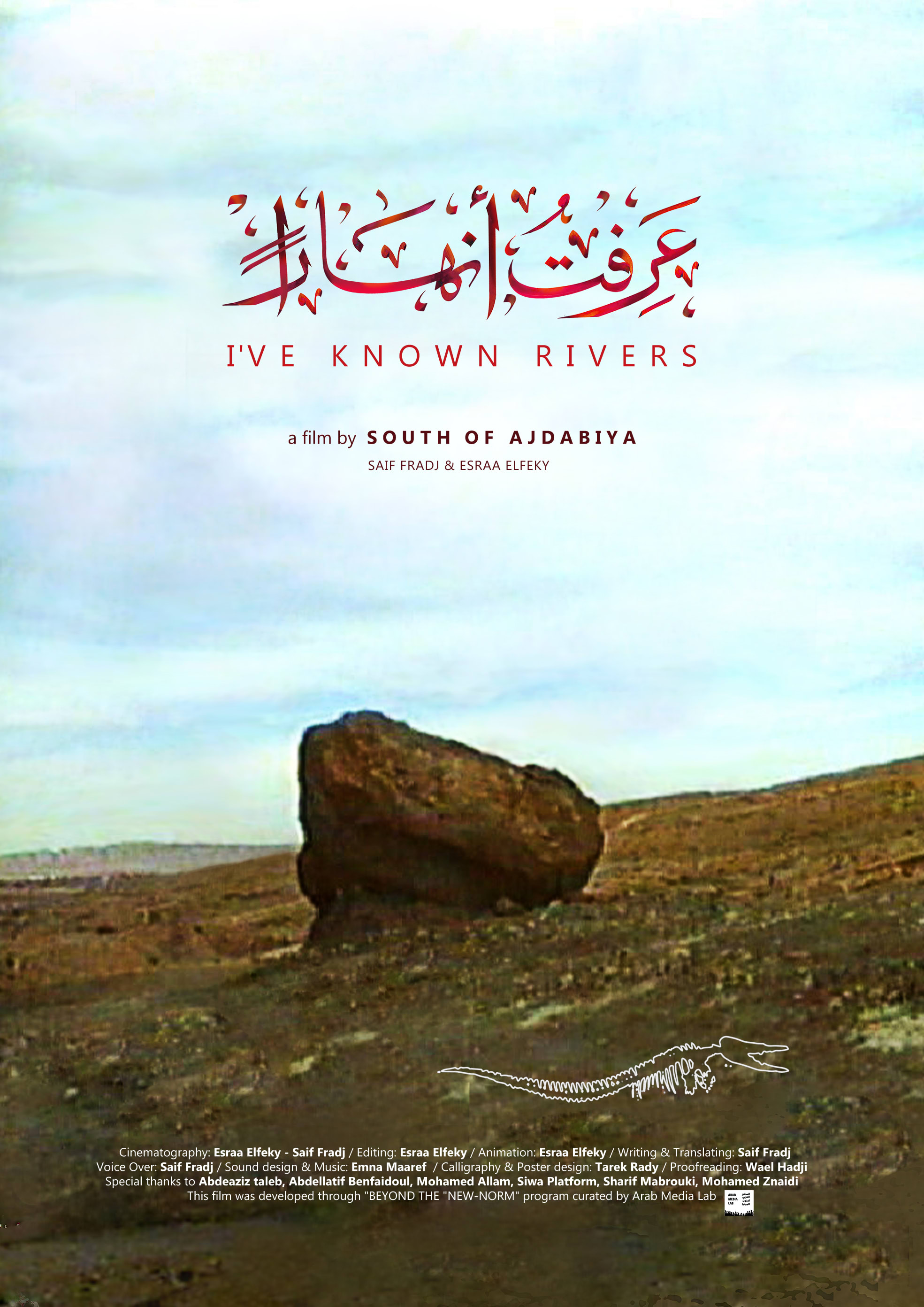

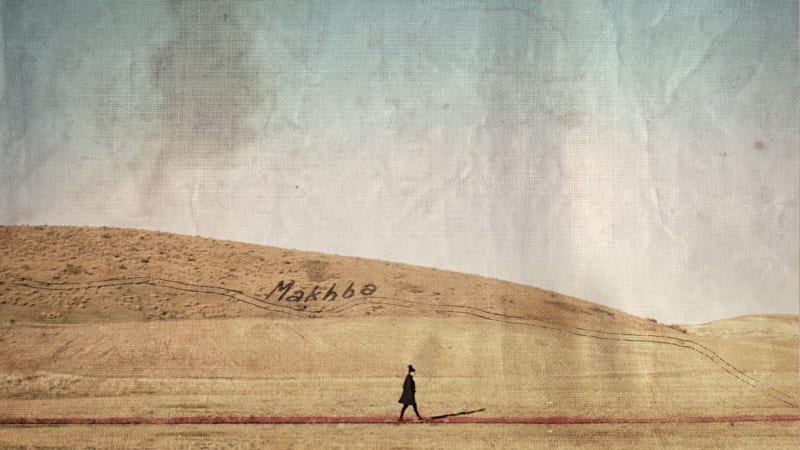

Saif Fradj, Esraa Elfeky

I’ve Known Rivers (2023)

Country: Tunisia

Runtime: 18’

“South of Ajdabya”, founded by Esraa Elfeky from Egypt and Saif Fradj from Tunisia, is a 2022

made collective of filmmakers interested in the north African desert, its mythologies, geologies,

and anthropology. Using a mix of old filmmaking techniques (analog) with digital drawings and

contemporary audio-visual effects, the collective aims to rewrite a common lost memory of the

North African region on which the subjective imagination interacts.